John Pickering

Local writer and storyteller, George Murphy interviews local characters and personalities

Introduction

John Pickering, long time Hebden Bridge resident, was born in Blackburn in 1939, attended Skipton Grammar School, studied Law at Leeds University and went on to become a champion of workers claiming compensation for industrial injuries and diseases . He is especially renowned for his trail blazing work on behalf of those affected by asbestos. It was John who first recognised that Acre Mill in Old Town was the site of the largest disaster in Britain's industrial history.

John Pickering, long time Hebden Bridge resident, was born in Blackburn in 1939, attended Skipton Grammar School, studied Law at Leeds University and went on to become a champion of workers claiming compensation for industrial injuries and diseases . He is especially renowned for his trail blazing work on behalf of those affected by asbestos. It was John who first recognised that Acre Mill in Old Town was the site of the largest disaster in Britain's industrial history.

During our meetings, I discovered that John is a keen linguist, a hobby which came in useful during cycling holidays with his wife Margaret. In retirement, the couple continued to cycle in England and in Europe , spending time with family and friends and John has continued to take a close interest in the vital work and the continuing plight of those affected by asbestos around the world.

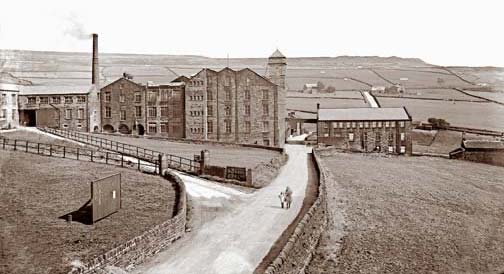

Acre Mill, Old Town

John Pickering cycled up to Old Town one weekend and, as a solicitor for the Thompsons firm, which supported workers affected by industrial injuries and diseases, he wondered why no claims had been reported by employees at Acre Mill asbestos factory.

In time, one client did make contact but he eventually decided that he didn't want to claim as he couldn't face being confronted by the personnel officer. Soon however a small trickle of cases came forward which grew rapidly into a deluge.

John contacted the Sowerby MP Douglas Houghton, a member of Harold Wilson's cabinet, who said he knew the manager at Cape Asbestos and he would check out what was happening. The manager reassured him but when John showed Houghton the death certificates of employees he became supportive.

It was Max Madden, successor to Houghton who became instrumental in getting the Ombudsman involved. The Ombudsman Enquiry was set up by The Minister of Employment, Michael Foot. This led to a damning report on the Factory Inspectorate.

By then John Pickering had calculated that the number of fatalities at Cape's Acre Mill site, since it's founding in 1939 made it the biggest industrial disaster in British history.

In time his initial estimates were exceeded with the discovery that mesothelioma, an incurable lung cancer, was usually related to contact with asbestos.

George Murphy interviewing John Pickering

Supporting Clients

In our meetings and telephone conversations John helped me by spelling out the technical terms for different types of industrial diseases and materials. I gained some insight into his approach in handling each new case in a methodical and exhaustive manner to support his clients. John's wife Margaret told me that for many years the large dining room table we were sitting at was covered by case files, reports and legal documents. They were also piled up on the surrounding floor.

John was keen to mention the dedicated work of his colleagues over the years and the ones who are still supporting the victims of asbestos.

John's firm pioneered compensation for sufferers of byssinosis caused by cotton dust starting with a mill in Elland. They were also involved with social and disablement benefits and other industrial disease cases across England.

One day he received papers through the post from an unidentified source regarding asthma and other conditions caused by the chemical Azodicarbonamide which is often used as a whitening agent in bread but was also used in plastic such as yoga mats.

In 1979 he set up John Pickering and Partners in Oldham. Later he opened an office in Manchester with two partners followed by other offices in Liverpool, Bradford and Halifax. The firm was growing quickly to meet the number of cases but it is the claims by individual workers that have remained in his mind.

In 1982 a documentary film Alice a Fight for Life was released by Yorkshire Television.

At this time I had moved with my wife and infant daughter from Hebden to Soyland where Peter our next door neighbour told me he had taken early retirement after being diagnosed with asbestosis. This despite only working at Acre Mill for one summer during his student days in the 1950s. Two years later we heard that Peter had died. That year we watched the documentary film about an asbestos case.

At this time I had moved with my wife and infant daughter from Hebden to Soyland where Peter our next door neighbour told me he had taken early retirement after being diagnosed with asbestosis. This despite only working at Acre Mill for one summer during his student days in the 1950s. Two years later we heard that Peter had died. That year we watched the documentary film about an asbestos case.

John's key role as her solicitor in the Alice Jefferson court case is captured by Stephen Sedley in 'Law and the Whirligig of Time' (2018, Bloomsbury press). Sedley was one of two barristers dealing with the case. He later became a Court of Appeal judge.

'As a teenager Alice Jefferson worked at Acre Mill, the asbestos factory in Hebden Bridge . There was loose asbestos all over the place: they skylarked and made wigs out of it.

"Now in her forties, she has mesothelioma, the asbestos cancer and she is dying. John Pickering, her solicitor has broken all records and got her case into court within a few months of issuing the writ. He wants a judge to see what happens to the victims, not just read about it when it's all over bar the dependency.

"It takes Alice Jefferson ten minutes to get up the steps to the courthouse. Every movement is pain. She ought to have died by now, says the physician who has come to give evidence for her. Even with her sunken face and unnaturally bright eyes she is a handsome person. She has kept all her remaining strength to tell her story to the judge, and she does it with clarity and determination. Whatever they say she does not intend to die. She has a teenage son and a little girl of four.

"The boy can cope though he says he doesn't mind how ill she is if she'll only live. The girl – her husband does his best, but he won't be able to do her hair properly for school. Sitting behind my leader, the gentle and able David Turner-Samuels, I am blinded by tears. Nobody must see.

"The judge awarded Alice the most he could but it was nothing . . . her wages were limited to a few years as a part time cleaner. And what price can anyone put on the pain in her side and in her heart.'

John Pickering vividly recalls going to Alice's terrace house before the court case.

"Alice had used post-it notes as reminders to her son, for after she had gone, to hang towels up on the bathroom rail and not leave them on the floor for example."

Alice died three months after the trial. She was 48 years old. The World in Action documentary The Dust at Acre Mill (the title had to be changed as requested by the defence lawyers from Getting Away with Murder) and the Yorkshire television film Alice - a Fight for Life spurred the campaign to ban asbestos.

Eyes Wide Shut

It was partly because of self interest and also because of the slow insidious effect of asbestos dust inhalation that some manufacturers chose to deny the fatal consequences of working with the toxic material.

Asbestos is a mixture of fibres, mineral and vegetable. John Pickering discovered that mesothelioma was recognised and regulated in the 1930s in Hitler's Germany. Before that, UK factory inspectors who were often female doctors, sent out reports from 1900 saying that asbestos caused damage to the lungs.

In 1933 the government commissioned a report from Dr Merewether which indicated the need for efficient dust extraction. The knowledge of asbestos causing cancer emerged in the 1950s in England. The effects of these cancers are often not recognised until 30 to 50 years after exposure. Dr Merewether recommended that more stringent safety measures should be followed. John explained that the Wagner investigation in the late 1950s was a devastating development linking asbestos to mesothelioma which can be caused by only slight contact with asbestos dust.

Ten Quid Poms

Cases were eventually being reported amongst former UK workers who had moved to Australia after taking the opportunity offered by the Australian Government to move to a new life and job for the price of a £10 pound passage. Legal cases against former employers in the UK had to be brought in England. So John went to speak to clients on the other side of the world and spoke about his work at a conference there. One client was a Bristol Rovers fan who told him he had emigrated in the middle of our winter and was wrapped up in woollies when he disembarked into the middle of an Australian summer!

Supported by Australian lawyer Armando Gardiman, John had a meeting with a client in Woy Woy – birthplace of Spike Milligan.

When she learnt of my interest in the subject Frances (Fay) Robinson of Mytholmroyd who worked for John's firm (he described her as 'a terrier' for tracking down information to support casework) lent me Magic Mineral to Killer Dust by Geoffrey Tweedale which includes the moving and angry response of a woman who worked for Turner and Newall in Rochdale before moving to Australia.

"Damn You, Turner Brothers. I am in control now. What a bastard - fresh, gritty, sticky fluffy blue asbestos sits there all so quietly for around thirty years then says, 'Here I am, nasty and deadly'.

I have to get this down on paper while my mind is in shock. It will be too bloody scary later on. I need something to fight with to make me strong again. I'm just not ready to give up. I like living. . . [but] l have to tell my children and my parents who are both alive, in their eighties . . . that I have been cheated out of thirty or more years.

That's thanks to you, Turner Brothers. We worked for you in the fluffy, blue snow. You never said it got on your lungs and just lay there for twenty to thirty years. You knew something because you gave us all those X-rays early on. But no masks, as we had to spit on our fingers to make it stick quick. We were on piece-work, remember. I damn you and blue asbestos as it grows like buggery in me.

Why were we not told about this? Why! Damn you Turner Brothers."

Independent, 25 November 1997.

USA & UK

John's office was winning cases for a while against the firm Turner and Newall.

"Thousands of documents – court orders – could be obtained more easily in America."

In England the process was more cumbersome. He said, "Turner and Newall wouldn't comply." J.W. Robert's, a subsidiary of Turner and Newall, eventually delivered the necessary documents three weeks before the trial, hoping for an adjournment.

"It was impossible to read thousands of documents in three weeks."

John and two barristers read as much as they could and gained the vital information that the firm had not been using the legally required dust extraction masks. The company wanted to kick the trial into the long grass but John knew it was vital to keep to the trial date – not least because clients might die during an adjournment. There was a practice back then where more prestigious law firms would try to move their clients up the list of trial dates.

"The judge, Mrs Justice Heilbron, demanded 'No prioritising, no fiddling the list!' "

British journalists noticed the stark disparities between the awards given to victims in the States and those nearer home. High profile cases such as that of the death of Steve McQueen, who had once lagged the pipes in battleship boiler rooms during the war, also alerted the public to the fact that asbestos could endanger lives in a range of occupations.

John's partner dealt with a case of a bus conductor who had contracted the disease by breathing in the fibres from the clothes of workers. His only known contact with asbestos was taking fares from passengers on his bus route from the Turner and Newall factory in Manchester to the city centre. At that time, there were few specialist physician consultants in England who would recognise mesothelioma. One was Mr Robin Rudd and in Halifax the consultant Bertram Mann. Both referred cases.

The South African Connection

Cape Asbestos, the owners of Acre Mill, were an English firm who had business in South Africa. The judges in The House of Lords, now called The Supreme Court, decided that the case for these victims of asbestos dust exposure could be brought in England.

John went to Johannesburg and Cape Town to advise on cases. He visited Prieska, a beautifully preserved Dutch style town where a university professor had ignorantly taken a party of 20 students on to an asbestos tip located on the outskirts of the town despite asbestos floating in the air!

Black people lived in a shanty town in a region of semi desert near the banks of the Orange River. Women were employed using hammers to free asbestos from rocks. John met black people who had no conception of the meaning of compensation. He spoke to Dr Wagner who couldn't understand why cases occurred in one part of a black township but not in another until he discovered that sufferers had been trying to dig for gold in the nearby asbestos mountains which were nearer to their homes.

Back Home

Back in England John used to travel from Hebden Bridge to watch Leeds United at Elland Road. One Saturday he noticed what looked like a wad of asbestos waste near the entrance to a stadium which attracted 20,000 people on match days. Angry about so many lives being imperilled he sent a sample of this in an envelope to a local health and safety inspector who contacted him and told him in no uncertain terms never to do such a thing again!

"He was right!" John admits but he had made an important point. People were contacting asbestosis and mesothelioma from lagging on pipes in boiler rooms and from notice boards in schools. As I write, research has revealed that there have been 150 cases recorded in the last 5 years due to contamination in school buildings.

People in Hebden Bridge and Mytholmroyd will know of cases where the spouses of former Acre Mill workers have died after years of washing their partners' overalls.

John still worries about the safety of the old Acre Mill site after a former Cape employee told him that materials were buried in underground ducts and pipes and he hopes that cases will not arise from this source.

John remembers a case where a woman in Dagenham contracted mesothelioma when sitting outside her new house in the sun when other houses were being built nearby. She could not have known it at the time but the houses were being built on asbestos contaminated land.

Not all John's work on behalf of asbestos sufferers was successful. One man was infected after playing on the Scout Road tip in his youth but he was denied compensation on the grounds that Cape could not have known at that time about the potential hazard from dumping materials there when the exposure happened. Whereas in County Durham, a man got compensation because, in his youth, he had often fired an air rifle on an asbestos dump near to the Turner and Newall factory.

John is also troubled by the case of Le Clemenceau, a French battleship from which was stripped in Hartlepool of 700 tons of asbestos in 2009 by the Able company. This, despite other countries turning the vessel away and the French refusing to do it. So far there haven't been cases arising from this work but we know it can take decades before mesothelioma is diagnosed.

John Pickering and Partners' important work has continued since John's retirement in 2004. At the retirement party (see above), Frances Robinson of Mytholmroyd, his friend and colleague, wrote that John's offices "had recovered millions of pounds in compensation for lung disease victims and their families."

Office Manager June Hand praised John's "hardworking, knowledgeable and humble approach." Many times, they had been surprised to see John on TV at home but he had never told them that it was going to happen. John expressed his great pride and satisfaction at the excellent work being continued by the partners in whose hands he was leaving the firm. They are now working under the name 'The Asbestos Law Partnership.'

See also: HebWeb Feature - Asbestos and the legacy of Acre Mill

More HebWeb interviews from George Murphy

If you would like to send a message about this interview or suggest ideas for further interviews, please email George Murphy