Richard Carter

Local writer and storyteller, George Murphy interviews local characters and personalities

The author of the acclaimed On the Moor, about his rambles over Wadsworth/Midgley moor, has written his own introductory comments:

The author of the acclaimed On the Moor, about his rambles over Wadsworth/Midgley moor, has written his own introductory comments:

I was born and raised on the Wirral, and studied physics, archaeology, and the history and philosophy of science at Durham University before embarking on a career in Information Systems, initially in a torpedo factory, then in the public sector. I finally moved to Hebden Bridge in 2001, where I live in a former farmhouse with my partner, a native Hebden Bridge lass.

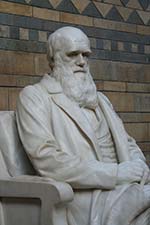

Thanks to George Osborne’s public sector austerity cuts in reaction to the private sector’s financial mismanagement, I eventually accepted, in the same month, both my long-service award and an offer of redundancy. My goal, as declared in my last ever staff appraisal, was to emulate my hero, Charles Darwin, by living in the countryside writing non-fiction books.

I’m currently working on a book about how Darwin looked at the natural world, and about how we can appreciate nature far better if we try to look at it as if through Darwin’s eyes.

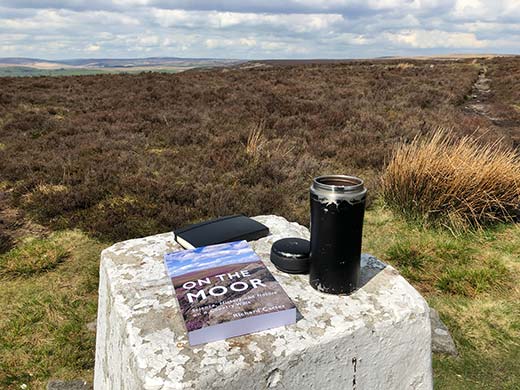

Sheep Stones Edge during 'Peak Purple'

(this photo features on the cover of On the Moor)

Richard Carter Q&A

Richard, I loved On the Moor. I’ll never contemplate Rooks or sunsets in the same way after reading it. What were your intentions when writing the book?

Thank you. I was really looking for an excuse to combine the three subjects that most interest me: science, history and nature. But I wanted to keep things personal and local, showing how there are scientific, historical and natural-historical stories to be found behind anything we might encounter on a walk on our local patch. My local patch is mainly moorland. I thought it would be an interesting challenge to see what stories I might unearth in an area that seems, on the face of it, to be little more than countless acres of heather with the occasional red grouse.

Can you describe how you first became interested in nature?

I have my late mum to thank for that. She loved the countryside, so the family took many weekend walks around the Wirral’s woods, hedgerows, and marshes when I was little. She bought my sister and me loads of nature books, and was always telling us the names of birds and flowers. Even over a decade after she died, my first instinct, whenever I see something new and exciting, is still to call mum. She would have been thrilled to hear about the barn owl that’s been patrolling the fields around our house for the last year or so.

A few years ago, the British public voted Winston Churchill the greatest Briton of all time. Charles Darwin came in 4th, just behind Princess Diana, but ahead of William Shakespeare. Can you make a case for your hero?

I was actually invited to appear in the studio audience for the BBC’s Great Britons final (in Andrew Marr’s Team Darwin corner, obviously), but I’ve never been a fan of beauty contests. That said, Darwin is clearly the correct answer. He came up with what has been described as ‘the single best idea anyone ever had’: the theory of evolution by means of Natural Selection. Darwin’s theory made the natural world make sense. It’s such a deceptively simple idea - so simple, you can explain the basic concept to a young child - but its implications are immense. It explains pretty much everything in nature: from the dawn chorus in your garden, to the spread of coronavirus; from why some snakes have hip-bones, to why foxgloves develop in the way they do. More importantly, perhaps, Darwin showed that all species, both living and extinct, are related to each other. We Homo sapiens are not separate from nature, but part of it. Darwin put us in our place. (He was also, incidentally, a hell of a nice chap.)

I was actually invited to appear in the studio audience for the BBC’s Great Britons final (in Andrew Marr’s Team Darwin corner, obviously), but I’ve never been a fan of beauty contests. That said, Darwin is clearly the correct answer. He came up with what has been described as ‘the single best idea anyone ever had’: the theory of evolution by means of Natural Selection. Darwin’s theory made the natural world make sense. It’s such a deceptively simple idea - so simple, you can explain the basic concept to a young child - but its implications are immense. It explains pretty much everything in nature: from the dawn chorus in your garden, to the spread of coronavirus; from why some snakes have hip-bones, to why foxgloves develop in the way they do. More importantly, perhaps, Darwin showed that all species, both living and extinct, are related to each other. We Homo sapiens are not separate from nature, but part of it. Darwin put us in our place. (He was also, incidentally, a hell of a nice chap.)

How has lockdown been for you?

It has affected me remarkably little, if I’m honest. I already worked from home, and am a natural introvert, so had little difficulty adjusting. I’ve missed being able to meet friends and family, but thank Apple for FaceTime!

What’s the good and bad of living round here?

I love the fact that, for such a small town, Hebden Bridge punches well above its weight. It has a well-deserved national reputation for being unlike other places. There is definitely a unique local vibe. The day after Trump’s inauguration, I attended a Caught by the River poetry and prose event at Machpelah Mill, in which a moving poetry recital by local poet Zaffar Kunial was interrupted by loud, forced laughs from the laughter-yoga session upstairs. I realised I had just experienced Peak Hebden Bridge. There’s not a lot I would like to change about living here, other than moving the town closer to the sea.

A red grouse on the Moor

How were your student days in Durham?

Mostly un-studious, if memory serves. I seem to remember beer was involved. I do remember spending three weeks on an archaeological dig in Shetland in March/April 1985. An unforgettable experience. I’ve just about thawed out.

What’s your taste in music?

I like to say I’ll listen to anything except Phil Collins. I have very eclectic tastes, but my favourite music is generally described as alternative - whatever that’s supposed to mean. Captain Beefheart, The Fall, Tom Waits, Radiohead, etc. Nearly every Friday for the last eight years, I’ve tweeted a link to a random Fall video with the hashtag #FallFriday in an attempt to educate the Fall-less Twitter masses.

We’re in a global pandemic and the world is warming. Are we all doomed?

As I explain in On the Moor, the Second Law of Thermodynamics means the universe itself is ultimately doomed. We’ve got through pandemics before, and we’ll get through this one - although not as quickly as we could have, had certain governments paid more attention to scientists. Global heating is a far bigger challenge. Science will do its bit, but the situation requires long-term thinking and action - and governments are notoriously bad at that. I’m sure, as a species, we’ll muddle through in the end, but the damage we’ve already done can only be mitigated, not undone.

George Monbiot has argued for the rewilding of the moors, allowing trees and bushes to replace the heather. What’s your view on that?

My gut feeling is it’s a good idea - although, obviously, I’d like some moors to remain. As with most initiatives, there are bound to be unforeseen consequences. For all I know, some of those might be beneficial too. But there are bound to be drawbacks. As Darwin said, ‘plants and animals, most remote in the scale of nature, are bound together by a web of complex relations’. Ecosystems are complicated. They seem to work best when left to their own devices, rather than being curated by well-meaning humans.

The barn owl that's been frequenting the neighbourhood

We’re nearing the Glorious 12th. Can you explain your current views on grouse shooting?

I don’t understand the mentality of killing wild animals purely for fun. Shooting organisations try to pass themselves off as custodians of the countryside. If that’s what they are, they’re exceedingly bad at it. In getting on for three decades walking on the local moors, I’ve only ever seen a single hen harrier. Moors are perfect habitats for hen harriers. Where are they all? It’s almost as if someone were killing them off - along with the other predators that threaten grouse numbers.

Richard Carter's only ever sighting of a hen harrier

on the Moor (October 2016)

You’re not a fan of wind turbines?

I see them as a dangerous distraction. Climate change is the single biggest threat to the natural world - including us. There are over 7 billion human beings on the planet. Demand for cheap energy will continue to grow, especially in the developing world. Renewable energy has its place, but it won’t be nearly enough. We need to be investing far more in reliable, low-carbon, high-yield energy sources, which currently means nuclear power. We should also be investing heavily in nuclear fusion research, which has the potential to produce vast amounts of clean energy. I appreciate my views on this matter are not very ‘Hebden Bridge’.

What makes you laugh?

I very much enjoy self-deprecating humour, whether it’s people laughing at themselves, or at the oddities of the groups to which they belong. If you can’t laugh at yourself, you need to reflect a bit more.

I’m grateful for the mixture of history and science in your writing, although I might have to reread your mathematical guide to not getting lost on the moors. Which authors have influenced your approach to writing non fiction?

The late, great American science-history essayist Stephen Jay Gould has been a huge influence on how I think - although he did go on far too much about baseball for my liking. There are many wonderful nature writers I admire, but my favourite is the Scottish poet Kathleen Jamie. Poets tend to have a wonderful, unpretentious precision when it comes to prose. They make it look effortless. Believe me, I know it’s not.

How’s your book on Darwin coming along?

Slowly, but surely. My first draft has just passed On the Moor in length. I have several more chapters planned. But it’s the second draft where the fun starts, and where books are made. I’ve learnt so much more about my hero as I worked on this book. I didn’t think it was possible, but the respect I have for Charles Darwin grows each day.

Which question do you wish I’d asked - and how would you answer it?

Question: Since you mention it, why do foxgloves develop in the way they do?

Answer: You’ll just have to wait for my Darwin book for an answer to that one.

Richard Carter at the trig point

More HebWeb interviews from George Murphy

If you would like to send a message about this interview or suggest ideas for further interviews, please email George Murphy